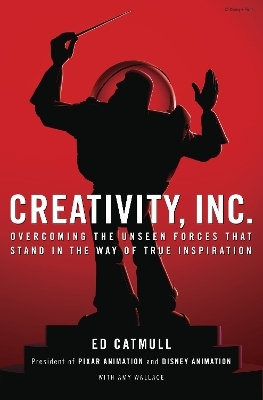

Creativity, Inc.

Random House USA Inc (Verlag)

978-0-553-84122-0 (ISBN)

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY

The Huffington Post - Financial Times - Success - Inc. - Library Journal

"What does it mean to manage well?"

From Ed Catmull, co-founder (with Steve Jobs and John Lasseter) of Pixar Animation Studios, comes an incisive book about creativity in business-sure to appeal to readers of Daniel Pink, Tom Peters, and Chip and Dan Heath. Forbes raves that Creativity, Inc. "just might be the business book ever written."

Creativity, Inc. is a book for managers who want to lead their employees to new heights, a manual for anyone who strives for originality, and the first-ever, all-access trip into the nerve center of Pixar Animation-into the meetings, postmortems, and "Braintrust" sessions where some of the most successful films in history are made. It is, at heart, a book about how to build a creative culture-but it is also, as Pixar co-founder and president Ed Catmull writes, "an expression of the ideas that I believe make the best in us possible."

For nearly twenty years, Pixar has dominated the world of animation, producing such beloved films as the Toy Story trilogy, Monsters, Inc., Finding Nemo, The Incredibles, Up, and WALL-E, which have gone on to set box-office records and garner thirty Academy Awards. The joyousness of the storytelling, the inventive plots, the emotional authenticity: In some ways, Pixar movies are an object lesson in what creativity really is. Here, in this book, Catmull reveals the ideals and techniques that have made Pixar so widely admired-and so profitable.

As a young man, Ed Catmull had a dream: to make the first computer-animated movie. He nurtured that dream as a Ph.D. student at the University of Utah, where many computer science pioneers got their start, and then forged a partnership with George Lucas that led, indirectly, to his founding Pixar with Steve Jobs and John Lasseter in 1986. Nine years later, Toy Story was released, changing animation forever. The essential ingredient in that movie's success-and in the thirteen movies that followed-was the unique environment that Catmull and his colleagues built at Pixar, based on philosophies that protect the creative process and defy convention, such as:

- Give a good idea to a mediocre team, and they will screw it up. But give a mediocre idea to a great team, and they will either fix it or come up with something better.

- If you don't strive to uncover what is unseen and understand its nature, you will be ill prepared to lead.

- It's not the manager's job to prevent risks. It's the manager's job to make it safe for others to take them.

- The cost of preventing errors is often far greater than the cost of fixing them.

- A company's communication structure should not mirror its organizational structure. Everybody should be able to talk to anybody.

Praise for Creativity, Inc.

"Over more than thirty years, Ed Catmull has developed methods to root out and destroy the barriers to creativity, to marry creativity to the pursuit of excellence, and, most impressive, to sustain a culture of disciplined creativity during setbacks and success."-Jim Collins, co-author of Built to Last and author of Good to Great

"Too often, we seek to keep the status quo working. This is a book about breaking it."-Seth Godin

Ed Catmull is co-founder of Pixar Animation Studios and president of Pixar Animation and Disney Animation. He has been honored with five Academy Awards, including the Gordon E. Sawyer Award for lifetime achievement in the field of computer graphics. He received his Ph.D. in computer science from the University of Utah. He lives in San Francisco with his wife and children. Amy Wallace is a journalist whose work has appeared in GQ, The New Yorker, Wired, Los Angeles Times, and The New York Times Magazine. She currently serves as editor-at-large at Los Angeles Times magazine. Previously, she worked as a reporter and editor at the Los Angeles Times and wrote a monthly column for The New York Times Sunday Business section. She lives in Los Angeles.

Chapter 1 Animated For thirteen years we had a table in the large conference room at Pixar that we call West One. Though it was beautiful, I grew to hate this table. It was long and skinny, like one of those things you'd see in a comedy sketch about an old wealthy couple that sits down for dinner-one person at either end, a candelabra in the middle-and has to shout to make conversation. The table had been chosen by a designer Steve Jobs liked, and it was elegant, all right-but it impeded our work. We'd hold regular meetings about our movies around that table-thirty of us facing off in two long lines, often with more people seated along the walls-and everyone was so spread out that it was difficult to communicate. For those unlucky enough to be seated at the far ends, ideas didn't flow because it was nearly impossible to make eye contact without craning your neck. Moreover, because it was important that the director and producer of the film in question be able to hear what everyone was saying, they had to be placed at the center of the table. So did Pixar's creative leaders: John Lasseter, Pixar's creative officer, and me, and a handful of our most experienced directors, producers, and writers. To ensure that these people were always seated together, someone began making place cards. We might as well have been at a formal dinner party. When it comes to creative inspiration, job titles and hierarchy are meaningless. That's what I believe. But unwittingly, we were allowing this table-and the resulting place card ritual-to send a different message. The closer you were seated to the middle of the table, it implied, the more important-the more central-you must be. And the farther away, the less likely you were to speak up-your distance from the heart of the conversation made participating feel intrusive. If the table was crowded, as it often was, still more people would sit in chairs around the edges of the room, creating yet a third tier of participants (those at the center of the table, those at the ends, and those not at the table at all). Without intending to, we'd created an obstacle that discouraged people from jumping in. Over the course of a decade, we held countless meetings around this table in this way-completely unaware of how doing so undermined our own core principles. Why were we blind to this? Because the seating arrangements and place cards were designed for the convenience of the leaders, including me. Sincerely believing that we were in an inclusive meeting, we saw nothing amiss because we didn't feel excluded. Those not sitting at the center of the table, meanwhile, saw quite clearly how it established a pecking order but presumed that we-the leaders-had intended that outcome. Who were they, then, to complain? It wasn't until we happened to have a meeting in a smaller room with a square table that John and I realized what was wrong. Sitting around that table, the interplay was better, the exchange of ideas more free-flowing, the eye contact automatic. Every person there, no matter their job title, felt free to speak up. This was not only what we wanted, it was a fundamental Pixar belief: Unhindered communication was key, no matter what your position. At our long, skinny table, comfortable in our middle seats, we had utterly failed to recognize that we were behaving contrary to that basic tenet. Over time, we'd fallen into a trap. Even though we were conscious that a room's dynamics are critical to any good discussion, even though we believed that we were constantly on the lookout for problems, our vantage point blinded us to what was right before our eyes. Emboldened by this new insight, I went to our facilities department. "Please," I said, "I don't care how you do it, but get that table out of there." I wanted something that could be arranged into a more intimate square, so people could address each other directly and not feel like they didn't matter. A few days

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.4.2014 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 8PP BLACK-&-WHITE PHOTO INSERT |

| Verlagsort | New York |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Maße | 154 x 233 mm |

| Gewicht | 414 g |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Kunst / Musik / Theater ► Film / TV | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Beruf / Finanzen / Recht / Wirtschaft ► Wirtschaft | |

| Wirtschaft ► Betriebswirtschaft / Management ► Spezielle Betriebswirtschaftslehre | |

| Wirtschaft ► Betriebswirtschaft / Management ► Unternehmensführung / Management | |

| Schlagworte | Animation • Autobiography • Biographies • Biography • books about business • business • business books • Business history • Communication • Creative thinking • Creativity • Culture • Disney • Entrepreneur • Film • Finding Nemo • Graduation • graduation books • graduation gifts • Innovation • inspirational books • Kreativität • Kreativwirtschaft • Leadership • leadership books • Management • management books • MONEY • Monsters Inc • Motivational books • nonfiction books • Pixar • Pixar Animation Studios • pixar book • Psychology • Steve Jobs • Technology • the incredibles • Toy Story • True stories • up • Wall-E • Wealth • Work |

| ISBN-10 | 0-553-84122-X / 055384122X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-553-84122-0 / 9780553841220 |

| Zustand | Neuware |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

aus dem Bereich