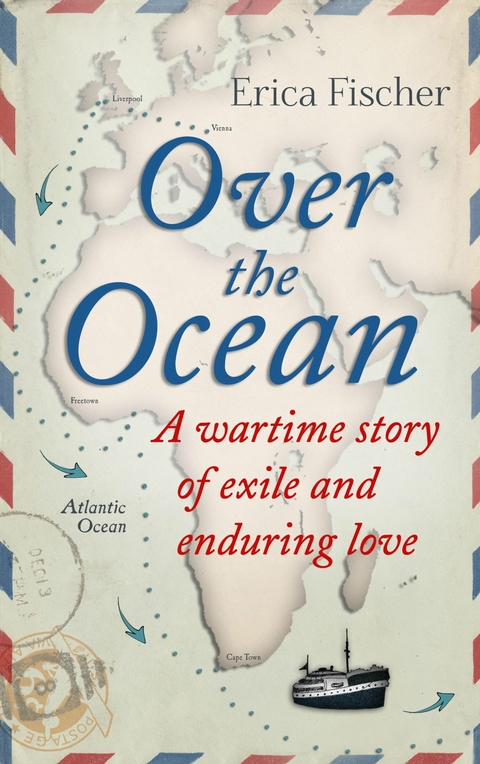

Over the Ocean (eBook)

224 Seiten

Hesperus Press Ltd (Verlag)

978-1-78094-308-4 (ISBN)

In July 1940, Erich Fischer found himself in Liverpool being herded onto a British transport ship bound for Australia, along with 2,500 other men. Conditions on board were horrific, with men locked below decks with overflowing latrines and only seawater to clean themselves. Separated from family, friends and removed from any semblance of a normal life, Erich is unsure whether he will ever see wife and child again. Erica Fischer's The King's Children tells the extraordinary story of her own parents and at the same time sheds light on a little-known and little-discussed chapter in British history. Fischer's parents met in Austria in the early 1930s. Her mother, Irka, was a Polish Jew and her father, Erich, was a Viennese lapsed Catholic. Faced with growing unrest in Europe, Irka fled to the United Kingdom in 1938, her husband followed a year later. However at the outbreak of war, Erich had been arrested as an 'enemy alien', and having been interned was deported to the opposite side of the world. Faced with unimaginable hardships, the deportees banded together in solidarity to face their new life in Australia and Erich was, against the odds, able to make contact with Irka and their letters established a lifeline between continents. The King's Children is astonishing true tale dealing with an unexposed and unexplored period in British history but also a story of the resilience of love.

When war broke out, Irka and Erich had to register with the English police and report once a week. They were asked to appear in front of a tribunal whose job it was to decide which German and Austrian foreigners were genuine refugees, and they blissfully imagined that they would be safe in refugee category C, officially classified as ‘refugees from Nazi oppression’. Irka’s case seemed cut and dried from the start, since she was Jewish, but Erich was lucky, because some tribunals did not realise that so-called Aryans could also be committed anti-Nazis.

About 600 people were placed in Category A. They were viewed, whether justifiably or not, as a higher level security risk and were immediately interned. About as many fell into Category B, and were subject to certain restrictions on travel. The vast majority, about 55,000 people, were recognised as refugees and could continue to move freely.

With a sigh of relief, Erich and Irka were able to continue working as domestic workers, the only activity allowed them. They were employed on a country estate in the south of England, in the hills of Wiltshire: Erich as a butler, Irka as a housemaid. They had food and a roof over their heads, and they were together. While Irka kept the living quarters clean, Erich’s job involved tidying up the billiard room and laying the table for the family of the house. As a boy from a working-class background, he had no idea where to put the fish knife and the dessert spoon. Holding a sketch that Irka had drawn for him, he just about got by.

They were not badly off in Wiltshire. Around the magnificent building there was nothing but rich meadows and herds of sheep, the family’s property with lush gardens and old English cottages with thatched roofs. On their days off they took trips into Shaftesbury and Salisbury. But the very idyllic quality of their lives was hard to cope with. With increasing concern they followed the progress of the war. They had lost all contact with their relatives. Erich’s father and his brothers in Vienna, and even more Irka’s parents and her younger brother in occupied Warsaw, lived in another world, now out of reach.

In the spring, Irka handed in her notice and moved to London. She had an opportunity to work there as a goldsmith, a profession for which she had trained at the Vienna School of Applied Arts, and she assembled a collection of her pieces. In Vienna she had started to earn good money for her work. She mainly designed silver jewellery – a successful blend of the Vienna workshop that had been founded at the beginning of the century and was dissolved in 1932 together with influences from her homeland. So she was fond of using the red coral so popular in Poland for the decoration of stylized flowers.

However, the British jeweller she was negotiating with expected a financial advance that she could not provide, and the matter fell through. In times of war, people have other things on their mind than buying jewellery. In May, Erich joined her: the promoter of appeasement, Neville Chamberlain, had just resigned as prime minister, and the charismatic Winston Churchill had formed a national coalition government.

It looked increasingly likely that Erich would be interned, so they decided for now to live on their savings and spend their remaining time together. Then, the mood gradually began to change. The British public had so far been well disposed towards the refugees, even when in January some tabloids blackened their name, calling them spies and saboteurs. A commentator from the left-wing New Statesman, Erich’s favourite magazine, expressed the view that the allegations had been put about by the army. The smears published in the Daily Express and the Daily Herald paved the way for a new direction in foreign policy. Erich spent his mornings reading the newspapers in the public library and making notes on whatever struck him as important.

The German army’s Fourth Panzer Division reached the French coast opposite England on 10th May, and the first Cabinet meeting of the new Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was held on 11th May. (And on 12th May the Royal Air Force started bombing German cities, the first of them being Mönchengladbach.) The item was listed on the agenda of the Cabinet meeting as ‘Invasion of Great Britain’. Home Secretary Sir John Anderson was asked by the British generals to clear the coastal area of foreigners, so Anderson immediately declared the entire east coast from Inverness down to Dorset to be a protected zone. Two thousand two hundred German and Austrian men between sixteen and sixty who lived in this region were ‘temporarily interned’ as it was called. Among them were tourists who had the misfortune to have been taking a Whitsun weekend trip to the seaside.

When the Netherlands surrendered, all male Germans and Austrians in category B were quickly arrested and escorted by soldiers in close formation to a detention centre. ‘Act! Act! Act! Do it now,’ cried the title of a report in the Daily Mail on 24th May. Erich anxiously saw that even reputable newspapers like The Times were adopting the same line.

‘We have to be prepared,’ he warned Irka. ‘And don’t you place your charms at the disposal of any men working in the munitions industry during my absence!’

Irka looked at him, puzzled.

‘Here, read this. I’ve copied it down for you from the Sunday Chronicle: “There is no dirty trick that Hitler would not pull, and there is a very considerable amount of evidence to suggest that some of the women – who are very pretty – are not above offering their charms to any young man who may care to take them, particularly if he works in a munition factory or the Public Works.”’

She laughed. But as if the newspaper had arranged it, 3,000 women in Category B were next day interned on the Isle of Man.

After the withdrawal of British troops from Dunkirk, a night curfew was imposed on all foreigners, with the exception of the French. Racist propaganda against ‘local Italians’ living in England had already been published for some time: the Daily Mirror was particularly outspoken. In one article, it described the 11,000 Italians living in London as ‘an undigestable unit of population’, despite which ships would continue to wash ashore ‘all kinds of brown-eyed Francescas and Marias, beetle-browed Ginos, Titos and Marios.’ A storm was brewing in the Mediterranean, and ‘even the peaceful, law-abiding proprietor of the backstreet coffee shop bounces into a fine patriotic frenzy at the sound of Mussolini’s name’.

Erich and Irka were horrified to experience xenophobia in England too, having just escaped it in Austria.

After Mussolini’s declaration of war on England and France on 10th June, Italians were arrested and anti-Italian sentiment resulted in attacks on Italian shops and cafes. British domestic intelligence put together lists of allegedly dangerous persons who were rounded up at dawn by police officers. Eventually, 4,500 Italians were arrested and interned, including many who had lived for decades in England, whose sons had been born there and were serving in the British Army. The writer George Orwell complained that you could not get a decent meal in London any more because the chefs of the Savoy, the Café Royal, the Piccadilly and many other restaurants in Soho and Little Italy had been locked up.

Cheered on by Churchill’s rallying cry ‘Collar the lot’, that at first no one took really seriously, the authorities interned ever more innocent German and Austrian men from the second half of June onwards, without even bothering to point out that this was just a provisional measure. The public was led to believe that the detainees were persons who had aroused suspicion in some way.

This was what angered Erich the most. He knew people whose health had been permanently damaged in Dachau and were now again being put behind barbed wire. At the same time, no one thought of interning a British demagogue like Sir Oswald Mosley, whose gangs of fascist thugs had provoked riots in the predominantly Jewish East End of London. Erich had no illusions that his impeccable political background could still protect him now.

Anderson had a standard formula ready to silence any criticism of the practice of internment. ‘I am afraid that hardship is inseparable from the conditions in which we live at the moment.’

Fear of a German invasion had gripped wide circles of the population. Increasingly, the call rang out, ‘Intern them all!’ There was a rumour going around that the royal family had fled to Canada, and children whose parents could afford it were evacuated in thousands. Although negotiations with Canada and Australia to accept refugees were secret, the news was leaked that the government was thinking of shipping ‘enemy aliens’ overseas.

So it is that Erich and Irka are prepared for the police to come knocking at their door. Their packed suitcase has been ready for days. They have considered how they can use the ‘unavoidable measure’ of internment to their advantage. If the men are to be sent overseas, they have agreed that Erich will hand himself in, provided Irka can follow him soon. In the Dominions, far away from the battlefields, an opportunity for them to be released will probably arise. After years of persecution, first by the Austro-fascists, then by the Nazis, they only want one thing: to live together in peace and freedom.

The approaching farewell is nevertheless difficult. Irka sobs: she has lived through too many separations in recent years. Her pregnant...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.6.2014 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | Andrew Brown |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78094-308-3 / 1780943083 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78094-308-4 / 9781780943084 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich